Caleb Crain, in his essay “Counter Culture: Fighting for literature in an age of algorithms” (Harper’s Magazine, July 2015), shares a delightful anecdote of literary subversion:

Caleb Crain, in his essay “Counter Culture: Fighting for literature in an age of algorithms” (Harper’s Magazine, July 2015), shares a delightful anecdote of literary subversion:

I worked in the town library when I was in high school, and one of the librarians, a former nun, used to wander through the stacks from time to time and save her favorite books from being discarded by stamping them with false due dates.

This in the context of “what you might call the working myth of the life of literature – the half-conscious way that people decide which texts they consider literature, and how they carry those texts forward.” Or in other words, a discussion of what it means to have literary canons at all: of what good they are and how they are best established and nurtured.

![images[7]](https://brettalansanders.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/images7.jpg?w=500) In the build-up to addressing those questions he mentions the early 19th-century English Romantic poet John Keats, he of the “Ode to a Grecian Urn” which many of us probably encountered in high school. In the spirit of his belief in literature’s power to transcend time and space (this in an era long before commercial transatlantic flights, let alone email, Facebook, and Twitter), Keats once proposed to his brother, from whom he was then separated by thousands of miles and by several time zones, that they each read Shakespeare at 10:00 Sunday mornings so they could each feel the other’s presence. And later, while bedridden with the tuberculosis that in a year almost to the day – when he was not yet twenty-six – would finish killing him, he proposed something similar to his lover Fanny Brawne: “Do not send any more of my books home. I have a great pleasure in the thought of you looking on them.”

In the build-up to addressing those questions he mentions the early 19th-century English Romantic poet John Keats, he of the “Ode to a Grecian Urn” which many of us probably encountered in high school. In the spirit of his belief in literature’s power to transcend time and space (this in an era long before commercial transatlantic flights, let alone email, Facebook, and Twitter), Keats once proposed to his brother, from whom he was then separated by thousands of miles and by several time zones, that they each read Shakespeare at 10:00 Sunday mornings so they could each feel the other’s presence. And later, while bedridden with the tuberculosis that in a year almost to the day – when he was not yet twenty-six – would finish killing him, he proposed something similar to his lover Fanny Brawne: “Do not send any more of my books home. I have a great pleasure in the thought of you looking on them.”

“What does it take to believe in such a communion?” Crain asks.

I think it requires the belief that reading, or at least a certain kind of reading, is sensuous, invisible, and soulful. Each instance of this kind of reading is unique. In its ideal form, it occurs on a plane that is oblique to the physical location of the people doing it, even when they happen to be in the same room.

Anyway, while not in favor of a narrowly selected canon, carved in stone, Crain argues that “some notion of a literary canon was essential to the ideal of soulful reading, because not all texts repaid soulful attention.” This becomes a question, then, of how to read literature: how to make judgments about it and how to distinguish between good and bad, better and worse, informed or thoughtful and uninformed or thoughtless.

How, in any case, does a reasonably flexible and evolving canon of the better kind of writing get established? “In my imagination, at least,” he writes, it has always been created by an elite, but not necessarily

any particular sociopolitical elite. Anyone who could persuade another person to listen to her literary opinion belonged. It was a kind of freemasonry, crossing time as well as space. Though some communications were transmitted instantly, others might not reach another member for years, perhaps centuries.

In respect to that latter possibility of centuries-delayed literary connections, Crain also addresses H. J. Jackson’s belief, expressed in her book Those Who Write for Immortality, that a literary reputation is not necessarily built on merit alone “but also by quirks of publishing history, unforeseeable shifts in readerly tastes, and acts of advocacy and partisanship.” To anyone writing for immortality she would propose, among other things, tasking some younger relative with the management of their estate and with the creation of “a personal myth contradictory enough to keep biographers occupied.”

“Jackson considers the canon a bit of a sham,” Crain adds, “and potentially dangerous.” He disagrees with her on this point because, among other things, even if she were to demonstrate the worthiness of an author previously excluded from the canon, she wouldn’t overthrow but merely refine that canon; because it “has long been understood to be an imperfect and continuous approximation.” Its very instability, in fact, “is part of the myth’s appeal, solacing authors who feel underappreciated – who hope that the judgment of posterity in, say, 2015 might be revised come 2050. The canon is a mystical sum,” he concludes, “which can never be tallied: its only true index is written in living and fallible hearts.”

#

As one of those writers who from time to time has felt underappreciated, I am “solaced,” to borrow Crain’s usage, by the notion that my day might yet come – never mind that when it finally does I might be decades or even centuries dead.

This speaks to an old vanity of mine which began in earnest approximately three and a half decades ago when I was just returned from a Mormon proselytizing mission in Argentina. But it had already taken shape before I hit the ground in that country; and was more vaguely intuited when as a senior in high school, after a series of miserable attempts, I finally wrote a short story worthy of the accolades of my creative writing teacher; who told me it was one of the two best she had seen, in her several years of teaching, from a student at that level.

She first goaded me by writing, at the top of a particuarly execrable attempt at a comedic imitation of the adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza: “A Cervantes you’re not.”Oh yeah? my offended pride soon told myself. I’ll show you! And then spent the necessary weeks, between school and home, crafting my definitive literary response. And while I understood that what I had pulled off was still not quite on the level of the great master Miguel de Cervantes, I began to think that maybe I could eventually write something of comparable worth.

The other story, undoubtedly superior to mine at least in execution but probably also in other respects, was a stream-of-consciousness piece after the fashion of Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall,” which my classmate (a junior) would have read in Miss Meadors’s non-elective English class that school year. In particular hers would not have been burdened, as mine was, by rampant sentimentality and a painfully naive religious sensibility.

Mine, the ingenuous narrative of a boy barely distinguishable from the self that wrote it, was at least in its best and central scene – fragmented somewhat clumsily by flashbacks – realistic and gritty. My fictional alter ego, in any case, after enduring years of bullying both physical and moral, took one last beating for chivalrous and perhaps heroic defense of a girl’s reputation and honor: the girl he loved but was too shy to tell her so. The story fairly dripped with the anguished sincerity of troubled adolescence and overwrought symbolism: the protagonist, as in a pre-writing exercise I had worked out to the finest detail, was named Peter Stone to reflect the disciple Peter’s name which represented the Rock the ancient Church was built on; and beyond that traveled through darkness to light, through the world’s wickedness to the borders of divine bliss, redeemed at last by his own determination and by the declared love (sealed with a chaste kiss) of his personal Dulcinea.

Within the first couple of years of my return from South America, anyway, simultaneously with my early and still tentative questionings of certain of the faith’s pieties and of the abyss between the appearance and essence of holiness, my literary conceit was fully in place: writing was for me a priestly vocation. It was my destiny, I felt certain, if only by sheer force of will, to become what in Mormon parlance would be “the great writer of the Restoration.” And I would surpass those faithful and believing writers who had come before me by virtue of my position as a virtual outsider, faraway from “the Mormon corridor” of Utah and its surrounding regions with their particular Western geography and cultures. I would do so at least at first – with my unique “insider-outsider” perspective, as a certain non-Mormon historian of Mormonism might put it – from back in Indiana where the early saints had scarcely left a trace; passing through on their route from New York and Ohio to Missouri and Illinois, final stops before the martyrdom of their first prophet Joseph Smith and the great exodus, under Brigham Young’s sure leadership, to the Salt Lake Valley.

By the mid to late Eighties, after several drafts of a novella and a set of related stories set principally in a geographically vague Latin American town called Magdalena, inhabited on its peripheries by missionaries, members, and converts to a millenarian “rainbow cult” founded on Joseph Smith’s elaborate take on the apocryphal lore of a prophet named Enoch (scarcely a footnote in the canonized book of Genesis); by this time, as I was saying, I had completed my first book-length manuscript: Saint Mary of Magdalene. Its central tale, simply “Magdalena,” was encouraged and guided through a thorough rewrite by an editor with a regional press specializing in history and culture (including Mormon history and culture) of the American West. But in the end, while he had many good things to say about it, he still thought my writing a bit heavy-handed in its witness of faith, my style having not quite attained the universal perspective and broad appeal of a Jewish narrative by Chaim Potok or Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Though one of the stories, called “Satyagraha” after Gandhi’s concept of “love-force” or “truth-force,” was modestly published by an undergraduate journal at Indiana University. It was modeled somewhat on the style of story-as-legend as exemplified by John Steinbeck’s The Pearl, and inspired at once by a written account of the ongoing slaughter of native peoples in Guatemala, and by my own acquaintance with a man who had formerly been a hitman in Argentina – for the military dictatorship of the late Seventies and early Eighties.

Later there would be (among various other projects including literary criticism, literary translation, and travel memoir) the still-evolving collection of stories called No One Assured in God, after a phrase by 20th-century Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. It includes stories based on episodes from my childhood, with nothing at all to do with my yet-future religious conversion, as well as others in which the Mormon universe plays, for the most part, only a peripheral role or in which Mormon lives are caught up in less explicitly faith-centered situations. Over the years the manuscript has dropped some stories and added others, and while the whole remains unpublished several of the stories have appeared in obscure (and now mostly defunct) print or online journals.

I submitted an earlier draft of the manuscript to a Utah publisher of unofficial and often controversial Mormon topics, and in the end one of the editors sent me the comments of two readers. One of them unhesitatingly recommended publication, stating that while some of the stories were stronger than others, it represented something new and original in Mormon letters, a distinct and often disturbing though always moral voice; and left him, on the whole, with such a powerful impression that he thought he could never forget some of its most affecting stories and images. The other, however, thoroughly trashed the manuscript and seemed to call into question my moral and religious character: he accused me, in particular, of an unseemly obsession with sex; not entirely fair, though some of the stories were, to greater or lesser degree, concerned with human sexuality.

For whatever reasons, the editorial team went with the latter recommendation. I confess that I didn’t understand why they should give preference to the most prejudiced and curmudgeonly reading, but there must have been others – principally, perhaps, the editors themselves – with their own hesitations. It seemed to me, in any case, that the other review, discounting some things but praising more, should have carried the day. I was in any case thrilled with its assessment. There is something to be said for rough edges, after all. Why, especially, should a debut performance have to be perfection itself?

Though in the end I tend to be rather a perfectionist, and if there was a will to publish it, I would by no means have shied away from further revision. Still, you can edit and refine forever: in some sense a text is only “finished” by virtue of its having finally been given up for publication.

As for the earlier collection, when I picked it up again recently and re-read it, I was surprised that it didn’t seem half as bad as I had come over the years to think it was. Its audience might have been fatally limited, but it too was certainly something new and wholly original in Mormon letters and thus deserved, I longingly thought, to stand in that company. I regretted that I hadn’t pushed a bit longer and harder; any little press, however small and insignificant, would have done.

#

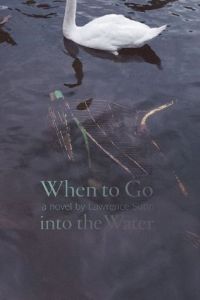

While reading the lines cited above from Caleb Crain’s Harper’s essay, I immediately thought of a slim volume called When to Go into the Water, written by Lawrence Sutin and published by Sarabande Books, an excellent small press from my neck of the woods in Kentuckiana (Louisville, to be precise). After pulling my copy off the shelf again, I went so far as to locate the November 7, 2010 journal entry that I had dedicated in part to it; and in which I first wrote about a book of poetry by Yehoshua November, a young Hasidic Jew whose faith-affirming and universally appealing verses evoked in me “that old yearning after holiness …”

“… a yearning, though, that is often satisfied in the most unlikely of places,” I wrote [and quote here with only the slightest edits], as in this little jewel of a novel whose sublime insights and wisdom are laced intimately with what would generally pass as the profane (which is not absent, by any means, in November’s book, though in those pages God’s presence is the source of healing; whereas here that source is a sensual and, it might seem, a-moral (a-theistic?) ethos of fleshly comforts and soothing waters.) The author’s conceit …

[and this is what I was reminded of by Crain’s text]

… is a kind of epigramic, scattered glimpse of the life and words of one Hector de Saint-Aureole, through his own travels and the parallel journeys of copies of his book – also called When to Go into the Water – which was printed privately in a small edition; and which we only glimpse from his point of view and from those of the various people who encounter the book.

In one passage one of his readers, a woman who had been seriously wounded by her relationships with men, after sitting down to read the book one night in a Starbuck’s, “poured the glass of water that the waitperson had brought with her coffee over her own head in response to the book’s admonition: ‘There is no prison so vast, so various in its tortures, as our own memories. Can we ever hope to be pardoned and released? But then, to whom are we pleading? We are the wardens of our own prisons. Wash the grime of the past from your skin and stand free in the present that is yours alone to live.’ The woman, who loved to read, let the water drip down her. The waitperson brought her a towel and asked if everything was okay. Inside herself the woman felt the water flowing into the cataracts of her heart.”

The passage, to me, was like a baptism of sorts, intensely moving, though in Nietszche’s sense, perhaps, of beyond good and evil – not, in other words, the baptism of any narrow religious (or secular, for that matter) dogma: “‘The drowning man looks upon water as the source of his doom,’ Hector wrote late that night. ‘The parched man sees it as the source of life. Water itself is without desire and washes all philosophies away.’” But not that this novel doesn’t suggest something of a latent ethical, if not narrowly moralistic, set of values, whether one think of them as humanistic or something else. Certainly, throughout, there is a hatred of war and all forms of violence against the human spirit. This is evident in a very early scene, by whose end the child Hector – in German-occupied France during World War I – has come to wish for “the war to slaughter the soldiers on both sides, as he already knew in his heart that all armies talked about love that way” – which is to say, falsely, cruelly. A later scene, which takes place in Argentina where Hector has fled to avoid the next European war, is so brutal that it took my breath away; but the shock is redeemed by this passage: “Hector didn’t so much as dare to write of it in his own book – only these three lines were entered that night as he smoked the American Lucky Strikes that were widely sold in Buenos Aires: ‘The war is everywhere. It was folly to hide. Leave Buenos Aires tomorrow and never linger anywhere again.’”

I still humor myself , now and then, with the secular promise of a kind of literary immortality that whether decades from now or centuries might yet come to pass, long after I am gone. Perhaps because of the diligence of a child or grandchild who kept the texts alive or even a more remote descendant who manages to bring them to a larger public. Or maybe, as in Hector de Saint-Aureole’s case, quite randomly and anonymously by the chance discovery of the rare copy of an old, privately-printed edition.

But I no longer suffer under the delusion of ever becoming “the great writer of the Restoration” or the epitome of anything. Though I still sometimes fancy that the literary work I do, original and in translation, matters in some critical sense; so that if not exactly a priestly profession, in some predominantly secular way those combined labors might be sainted.

#

In fighting for literature in this age of instantaneous counting and valuing of things, Crain identifies three temptations in regard to all things countable.

In fighting for literature in this age of instantaneous counting and valuing of things, Crain identifies three temptations in regard to all things countable.

First on that list “is to imagine that instances of [the thing] are interchangeable. The average, rather than the ideal, becomes the archetype.” This, Crain says, is the equivalent of saying, as a certain scholar of religious studies has claimed, that since “Jesus was one of a number of Aramaic-speaking magician-messiah figures with a revolutionary message in first-century Jerusalem,” then he obviously resembled the others and so a unified portrait of them all “would be tantamount to a portrait of Jesus. The trouble,” Crain insists, “is that even though such an assumption might be sensible in economics, it isn’t quite safe in history, and in religion it won’t do at all.” Nor, by implication, in literature.

Second, he writes, “is to imagine that no single instance of a thing matters – that the individual case is no more than a rounding error. In the old myth, by contrast, it was possible to believe that a work of literature succeeded if it reached just one person for whom it was a key.”

But third, he adds, “and perhaps most crucial,” is to equate value with popularity. And it is here that we come to the heart of the questions we started with: on the nature of judgment, of an established if ever-fluid canon (or set of canons).

This concept of instability that we discussed in relation to Jackson’s reservations on the subjecg “is being replaced,” Crain writes, “by an illusion of certainty. As I write this sentence, the Amazon sales rank of John Keats’s Selected Letters is 796,426, and the new Oxford Authors edition of William Wordsworth’s poetry and prose has a rank of 2,337,250.”

“Literature will survive,” he suggests at the end of an essay infinitely more involved and thoughtful than I can convey here,

if readers declare war on counting, if they insist that literature is defined by the judgment of the ideal critic and not the average one, and if they are able to build new communities of critics and readers with borders that are porous and expansive but nonetheless meaningful. “For this week past,” Keats wrote to Fanny Brawne, on July 4, 1820, “I have been employed in marking the most beautiful passages in Spenser, intending it for you, and comforting myself in being somehow occupied to give you however small a pleasure.” The communion imagined by Keats here is on a continuum with those he imagined in his other letters to Brawne or to his brother, but in this case no mysticism is required. As soon as Keats was healthy enough he would be able to visit Brawne and share with her the Spenser verses that he had marked. But I wonder if the sharing, when it took place, would have been able to bring him as much pleasure as his imagination of the sharing had. Or to put it another way, I wonder if what he would have most enjoyed, in the act of sharing, was his imagination of Brawne’s pleasure – which, even if she were sitting beside him, would have been invisible to him – and his imagined perception that it brought their souls together. The deepest literary pleasures, even when they involve others, are a little dreamy and lonely.