In the title essay of his book Notes of a Native Son (1955), the great American writer James Baldwin reflects on race relations in the United States – and more particularly, in Harlem – at the time of his father’s death in the summer of 1943, at a moment when Black Harlem was on the verge of an eruption of pent-up resentment and anger.

In the title essay of his book Notes of a Native Son (1955), the great American writer James Baldwin reflects on race relations in the United States – and more particularly, in Harlem – at the time of his father’s death in the summer of 1943, at a moment when Black Harlem was on the verge of an eruption of pent-up resentment and anger.

Those of you who have read Baldwin’s autobiographical novel Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), his first, are aware that his relationship with his authoritarian preacher father was not good. This remarkable novel, which when I first read it many years ago simply took my breath away, captures perhaps more evocatively than any nonfictional account could do the dynamics of that relationship. “Notes of a Native Son” picks up that relationship at a point when it is too late to make amends but when the author is ready to see his father in a more sympathetic light.

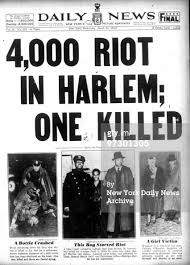

As the essay begins, he remarks on the coincidence that summer of his father’s death with two race riots in different parts of our nation: one in Detroit, over a month earlier, “one of the bloodiest race riots of the century”; and the other in Harlem, much less bloody, on the eve of his father’s burial.

“On the morning of the 3rd of August,” he writes at the end of one paragraph, “we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.”

And early in the next paragraph: “As we drove him to the graveyard, the spoils of injustice, anarchy, discontent, and hatred were all around us.”

Then, at the end of the same paragraph, this statement of one of the essay’s driving themes: “I had inclined to be contemptuous of my father for the conditions of his life, for the conditions of our lives. When his life had ended I began to wonder about that life and also, in a new way, to be apprehensive about my own” (Beacon Press paperback edition, 1990, pp. 85-86).

This apprehensiveness about his own life – this identification with his father’s suffering; with the suffering of all of Harlem and, by extension, all of Black America – may in fact be the essay’s principal theme: the recognition “that my life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart” (p. 98).

At this point it must be said that we could all stand to take a close look at our own hearts, to examine the acknowledged and/or unacknowledged hatreds that, to greater or lesser degree, at least potentially, we carry within us. These hatreds or their seeds, if they are hard to pinpoint, must be closely linked to those prejudices, acknowledged or unacknowledged, that we all possess. Just think about the issues, and the people, who make you most angry or afraid or resentful and you can’t be too far from the mark.

At this point it must be said that we could all stand to take a close look at our own hearts, to examine the acknowledged and/or unacknowledged hatreds that, to greater or lesser degree, at least potentially, we carry within us. These hatreds or their seeds, if they are hard to pinpoint, must be closely linked to those prejudices, acknowledged or unacknowledged, that we all possess. Just think about the issues, and the people, who make you most angry or afraid or resentful and you can’t be too far from the mark.

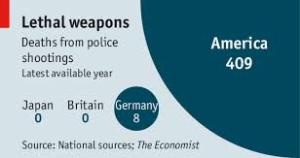

In the context of the hatred which at this point Baldwin has just begun to recognize, here we are more than half a century later in the shadow of Ferguson, Missouri, in what some would have us believe is a “post-racial” America. Our views are prejudiced, in this regard, when we instinctively blame the dead black man, who after all wasn’t “such an angel,” and absolve the white police officer whose first words to the unangelic Other were something like: “Get the f— onto the sidewalk!”

While we would resent it deeply and noisily – and perhaps violently – if the police in our own neighborhoods started cussing and routinely shooting our own adolescent sons and juvenile delinquents in the back and letting them die, even if they had seconds or minutes earlier resisted arrest and/or committed a petty theft.

Of course an automatic contempt against police, presuming their guilt in the instance of any shooting, can also be problematic. It is true, likewise, that no video can tell the whole story: what might have happened outside the frame, for example, or a few seconds earlier. But we will come back to that point.

In Baldwin’s case, the seeds of hatred for an oppressive White America began to show themselves after he had left his father’s home as a young man, striking out to make a literary reputation and instead being hit with the full force of blatant racially-motivated prejudice for the crime of being born black.

“That year in New Jersey lives in my mind as though it were the year during which, having suspected a predilection for it, I first contracted some dread, chronic disease, the unfailing symptom of which is a kind of blind fever, a pounding in the skull and fire in the bowels,” Baldwin writes. “Once this disease is contracted, one can never be really carefree again, for the fever, without an instant’s warning, can recur at any moment. It can wreck more important things than race relations. There is not a Negro alive who does not have this rage in his blood – one has the choice, merely, of living with it consciously or surrendering to it. As for me, this fever has recurred in me, and does, and will until the day I die” (p. 94).

“That year in New Jersey lives in my mind as though it were the year during which, having suspected a predilection for it, I first contracted some dread, chronic disease, the unfailing symptom of which is a kind of blind fever, a pounding in the skull and fire in the bowels,” Baldwin writes. “Once this disease is contracted, one can never be really carefree again, for the fever, without an instant’s warning, can recur at any moment. It can wreck more important things than race relations. There is not a Negro alive who does not have this rage in his blood – one has the choice, merely, of living with it consciously or surrendering to it. As for me, this fever has recurred in me, and does, and will until the day I die” (p. 94).

In this essay Baldwin describes the heavy stillness that rested over Harlem in the days and hours before the riot. “All of Harlem,” he writes, “seemed to be infected by waiting” (p. 98). One cause among several that he cites is World War II and the fact that “Negro soldiers, regardless of where they were born, received their military training in the south,” where for their service they suffered all of the indignities of Jim Crow. He writes of an increasing police presence and an increasing unrest – “perhaps, in fact, partly as a result of the ghetto’s instinctive hatred of policemen” (p. 99).

“I had never before been so aware of policemen,” he writes, “on foot, on horseback, everywhere, always two by two. Nor had I ever been so aware of small knots of people. They were on stoops and on corners and in doorways, and what was striking about them, I think, was that they did not seem to be talking. Never, when I passed these groups, did the usual sound of a curse or a laugh ring out and neither did there seem to be any hum of gossip. There was certainly, on the other hand, occurring between them communication extraordinarily intense. Another thing that was striking was the unexpected diversity of the people who made up these groups. […] that summer I saw the strangest combinations: large, respectable, churchly matrons standing on the stoops or corners with their hair tied up, together with a girl in a sleasy satin whose face bore the marks of gin and the razor, or heavy-set, abrupt, no-nonsense older men, in company with the most disreputable and fanatical ‘race’ men […] Seventh Day Adventists and Methodists and Spiritualists seemed to be hobnobbing with Holyrollers and they were all, alike, entangled with the most flagrant disbelievers; something heavy in their stance seemed to indicate that they had all, incredibly, seen a common vision, and on each face there seemed to be the same strange, bitter shadow” (pp. 99-100).

![images[3]](https://brettalansanders.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/images31.jpg?w=500) All of them had family or friends or lovers in the Army: “It would have demanded an unquestioning patriotism, happily as uncommon in this country as it is undesirable, for these people not to have been disturbed by the bitter letters they received,” Baldwin writes, “by the newspaper stories they read, not to have been enraged by the posters, then to be found all over New York, which described the Japanese as ‘yellow-bellied Japs.’ It was only the ‘race’ men, to be sure, who spoke ceaselessly of being revenged – how this vengeance was to be exacted is not clear – for the indignities and dangers suffered by Negro boys in uniform; but everybody felt a directionless, hopeless bitterness, as well as that panic which can scarcely be suppressed when one knows that a human being one loves is beyond one’s reach, and in danger” (pp. 100-101).

All of them had family or friends or lovers in the Army: “It would have demanded an unquestioning patriotism, happily as uncommon in this country as it is undesirable, for these people not to have been disturbed by the bitter letters they received,” Baldwin writes, “by the newspaper stories they read, not to have been enraged by the posters, then to be found all over New York, which described the Japanese as ‘yellow-bellied Japs.’ It was only the ‘race’ men, to be sure, who spoke ceaselessly of being revenged – how this vengeance was to be exacted is not clear – for the indignities and dangers suffered by Negro boys in uniform; but everybody felt a directionless, hopeless bitterness, as well as that panic which can scarcely be suppressed when one knows that a human being one loves is beyond one’s reach, and in danger” (pp. 100-101).

Describing later the scene at his father’s funeral, he speaks of an emotion that is undoubtedly present in Black American communities today; at this time, it seems, of ever-increasing incidents of black men or boys (mostly men or boys) being shot and killed by either police or stand-your-ground vigilantes:

“It was the Lord who knew of the impossibility every parent in that room faced: how to prepare the child for the day when the child would be despised and how to create in the child – by what means? – a stronger antidote to this poison than one had found for oneself.”

And in respect to his father: “With these several schisms in the mind and with more terrors in the heart than could be named, it was better not to judge the man who had gone down under that impossible burden. It was better to remember: Thou knowest this man’s faults; but thou knowest not his wrassling” (p. 106).

The riot broke out, on the night after the funeral, over a shooting stemming from a fight in a hotel over a black girl, the fight between a black soldier and a white policeman. “Rumor,” Baldwin writes, “flowing immediately to the streets outside, stated that the soldier had been shot in the back, an instantaneous and revealing invention, and that the soldier had died protecting a Negro woman. The facts were somewhat different – for example, the soldier had not been shot in the back, and was not dead, and the girl seems to have been as dubious a symbol of womanhood as her white counterpart in Georgia usually is, but no one was interested in the facts. They preferred the invention because this invention expressed and corroborated their hates and fears so perfectly. It is just as well to remember that people are always doing this. […] The effect, in Harlem, of this particular legend was like the effect of a match lit in a tin of gasoline. The mob gathered before the doors of the Hotel Braddock simply began to swell and to spread in every direction, and Harlem exploded” (pp. 109-10).

The riot broke out, on the night after the funeral, over a shooting stemming from a fight in a hotel over a black girl, the fight between a black soldier and a white policeman. “Rumor,” Baldwin writes, “flowing immediately to the streets outside, stated that the soldier had been shot in the back, an instantaneous and revealing invention, and that the soldier had died protecting a Negro woman. The facts were somewhat different – for example, the soldier had not been shot in the back, and was not dead, and the girl seems to have been as dubious a symbol of womanhood as her white counterpart in Georgia usually is, but no one was interested in the facts. They preferred the invention because this invention expressed and corroborated their hates and fears so perfectly. It is just as well to remember that people are always doing this. […] The effect, in Harlem, of this particular legend was like the effect of a match lit in a tin of gasoline. The mob gathered before the doors of the Hotel Braddock simply began to swell and to spread in every direction, and Harlem exploded” (pp. 109-10).

The damage was limited to Harlem itself, most of it to businesses owned by whites, and “might have been a far bloodier story, of course, if, at the hour the riot began, these establishments had been open.” The looting, Baldwin adds, was done “with more haste than efficiency,” and left an impression of stores “smashed open” and wealth (“the first time wealth had entered my mind in relation to Harlem”) “scattered in the streets. But one’s first, incongruous impression of plenty,” he adds, “was countered immediately by an impression of waste. None of this was doing anybody any good. It would have been better to have left the plate glass as it had been and the goods lying in the stores.

“It would have been better, but” (and here is the key thing) “it would also have been intolerable, for Harlem had needed something to smash. To smash something is the ghetto’s chronic need. Most of the time it is members of the ghetto who smash each other, and themselves. But as long as the ghetto walls are standing there will always come a moment when these outlets do not work. That summer, for example, it was not enough to get into a fight on Lenox Avenue, or curse out one’s cronies in the barber shops. If ever, indeed, the violence which fills Harlem’s churches, pool halls, and bars erupts outward in a more direct fashion, Harlem and its citizens are likely to vanish in an apocalyptic flood. That this is not likely to happen is due to a great many reasons, most hidden and powerful among them the Negro’s real relation to the white American. This relationship prohibits, simply, anything as uncomplicated and satisfactory as pure hatred. In order really to hate white people, one has to blot so much out of the mind – and the heart – that this hatred itself becomes an exhausting and self-destructive pose. But this does not mean, on the other hand, that love comes easily: the white world is too powerful, too complacent, too ready with gratuitous humiliation, and, above all, too ignorant and too innocent for that” (pp. 110-12).

Here it would be well, perhaps, to pause and take a deep breath.

The fact that these words still seem so pertinent nearly six decades later, that they still seem so vital at this moment just over five decades since the Voting Rights Act was passed by Congress, is to me at once disturbing, discouraging, and sobering. It is one thing among many that I lie awake some nights worrying about.

And along with the physical violence and routine humiliations is the fact that a majority of Supreme Court Justices can pretend that no teeth are any longer needed in that “antiquated” Voting Rights Act, turning a blind eye as a plethora of states immediately follow up with new voting restrictions that will predominantly affect poor black people and other minorities.

The ideal of Justice in this nation is not a wanton blindness to the plight of those among us who suffer, but a disinterestedness (in the sense of not favoring one over another while the facts of the matter are being established) between white or black, rich or poor, in its administration. How do we achieve this in a nation that lets billionaires buy Congress in the name (another questionable contribution of our Supreme Court) of freedom of speech: the corporation, and each of its billions of dollars, as person?

But I digress.

It is time we had a deep and sober national conversation about the latent racial animosity (call it “racism” or what you will) that permeates our society. It may not be conscious, among a vast majority of my fellow members of the white race, but to pretend it doesn’t exist is an exercise in mass self-delusion.

Let’s return to my earlier point about videos, both what they show us and what lies outside the frames of their limited space and time. This is true, but at least one half of the equation is that still they do show us something. And an almost constant, ceaseless supply of them purporting to show the same thing – that is, police behaving badly, violently, arrogantly, with deadly or crippling force against individuals who within their frame clearly pose no present danger to anyone – an endless flow of these images creates not only a perception of official wrongdoing but a clear indictment of police culture that allows these things, over and over again, to keep happening.

Let’s return to my earlier point about videos, both what they show us and what lies outside the frames of their limited space and time. This is true, but at least one half of the equation is that still they do show us something. And an almost constant, ceaseless supply of them purporting to show the same thing – that is, police behaving badly, violently, arrogantly, with deadly or crippling force against individuals who within their frame clearly pose no present danger to anyone – an endless flow of these images creates not only a perception of official wrongdoing but a clear indictment of police culture that allows these things, over and over again, to keep happening.

The point that I make here about police culture has also been made, in online accounts that I have recently read, by ex-policemen who have been examining the same problems from a new distance and recognizing their former selves in a less than glowing perspective. This is not to say that they were bad people, or that the majority of police officers are bad people, but quite the contrary. Police cultures are made and police cultures can be changed. We can examine, and begin to recognize, our prejudice and how that has affected our behavior. And how a change of attitude, of perspective, can change the whole dynamic on the ground.

The point that I make here about police culture has also been made, in online accounts that I have recently read, by ex-policemen who have been examining the same problems from a new distance and recognizing their former selves in a less than glowing perspective. This is not to say that they were bad people, or that the majority of police officers are bad people, but quite the contrary. Police cultures are made and police cultures can be changed. We can examine, and begin to recognize, our prejudice and how that has affected our behavior. And how a change of attitude, of perspective, can change the whole dynamic on the ground.

We do not have to become a police state, in other words, if we determine that we don’t want to. And the problem here, it should be stated clearly, does not rest solely with police departments but also with the criminal justice system from top to bottom (what Michelle Alexander calls “the new Jim Crow”), the political system that legislates it, and we the people who in our fear have sometimes cried out for it.

Consider, for example, the hysteria with which as a nation we greet the hordes of Central American children – refugees really, not immigrants, whom we think to treat humanely when we give them their bit of time before a judge (often without interpreters) before sending them back to their home countries where already numbers of them have been killed.

Consider, for example, the hysteria with which as a nation we greet the hordes of Central American children – refugees really, not immigrants, whom we think to treat humanely when we give them their bit of time before a judge (often without interpreters) before sending them back to their home countries where already numbers of them have been killed.

But I digress.

None of which, by the way, is to play the so-called “race card,” as conscious and unconscious deceivers alike are always saying. This is the same voice that accuses them, when the poor or middle classes complain that the wealth isn’t trickling down as for decades promised, of waging “class warfare” against the rich. These are specious and dishonest arguments, political red herrings that steal our attention away from the con job that if we let them the unscrupulous among us will continue to play on us.

The race card, if it is being played at all, is wielded by those who stoke people’s fears of the “racially” Other among us and who try to keep a majority of them from exercising their Constitutionally-granted political power – the very ones who then cry foul, in other words.

Likewise is “class warfare” being waged by the selfish (and arguably unpatriotic) 1% who, since the invisible “recovery” from the economic crash of 2008, have profited anywhere from 22 to 118 to 993 times more than those in the bottom 90% (according to a chart in the September / October 2014 Mother Jones) – the very ones who cry big crocodile tears and pretend that those demanding a “redistribution” of national wealth (the ones by means of whose sweat and blood the profits are made in the first place) of being “like the Nazis.”

No past civilization has ever allowed such a chasm between its wealthiest and poorest people to exist. No nation so divided can long stand – certainly not without the constant threat of violent upheaval.

But again, I digress.

And yet, no, not really. Because all of these concerns – race prejudice, social and economic and educational inequality, domestic and international violence, and all the other things I stay awake some nights worrying about – are intricately and inescapably related.

Be all that as it may, let me return, in closing, to the words of James Baldwin, whose essays have helped to give me a deeper perspective on this ever vexing “race problem.”

“It began to seem,” he writes at the end of his “Notes of a Native Son,” “that one would have to hold in mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s life, accept these injustices as commonplaces but must fight them with all one’s strength. This fight begins, however, in the heart and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair. This intimation made my heart heavy and, now that my father was irrecoverable, I wished that he had been beside me so that I could have searched his face for the answers which only the future would give me now” (pp. 113-14).

It is high time, it seems to me, that as a nation we stand together in demanding a closer alignment between the ways things are and the ways they might be.