At the City Winery in Chicago on Sunday, May 17, scarcely a week before this Memorial Day weekend, my son Jonathan and I attended a concert by Buffy Sainte-Marie.

Those of you of a certain age (or of a particular convergence of life experiences) may know her as a Native American singer-songwriter, a Cree Indian from across the United States’ northern border in Canada. Her music is an eclectic and totally unique mixture of folk and rock influences with indigenous sounds and vocal stylings, as well as other musical and lyric forms from around the world.

I first learned of her – I must have been about thirteen, just learning to play the guitar – from a slim Scholastic Books anthology of socially and ecologically conscious song lyrics from mostly the Sixties and the first year or two of the Seventies. It included – along with material by the Beatles, Pete Seeger, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Joan Baez, and Cat Stevens, among others – Sainte-Marie’s classic “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone.” My severely battered copy of the book, missing both covers and some of the inside material, contains the penciled-in guitar chords that my teacher Keith Craddock would have helped me work out. I must have heard the song first on his voice; it would be decades, in fact, before I heard it as re-recorded on her 1996 album Up Where We Belong.

The title song on that album, winner of the Oscar for Best Song in 1982, was recorded most famously by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes for the soundtrack of the movie An Officer and a Gentleman. In her simple acoustic version it feels like a whole different song, not unlike others of her tender love songs and to my ears much preferable to the orchestral flashiness of the other.

Opening for her in Chicago was a young singer-songwriter of Choctaw heritage from Shawnee, Oklahoma. Samantha Crain, alone with her acoustc guitar, performed a brief set of maybe half a dozen songs about the often heart-breaking experiences of ordinary people. She clearly has as much professional talent and potential as her elder Sainte-Marie, who at 74 still has a remarkably spry, almost acrobatic stage presence. The audience (an extremely warm group!) had a hard time saying goodbye to Crain, but of course everyone was ready when Sainte-Marie came on with her full band with electric guitars, bass, drums, and keyboard – as well as, for at least one number, her own acoustic guitar.

The song I am thinking of, which she performed alone while the band took a break, is “Universal Soldier”; it appeared originally in 1964 on her first album and was made famous by Donovan – and subsequently recorded by others including, decades later, country icon Glen Campbell.

It is an antiwar song, of course. Or, to put it more postively, a song promoting what she calls “alternative conflict resolution” from the national to international level. The song came about from her experience at an airport in San Francisco, I believe, where she saw wounded soldiers being brought home from a war that the U.S. government still insisted was not being fought. So she started thinking about circles of responsibility and the essential role of soldiers, without whose sacrifice of their bodies the wars could not be waged in the first place. And about the insanity of believing that war can be put an end to in that way.

The song became a call of conscience, then, to the universal soldier who “really is to blame” but whose “orders come from far away no more.” Not that she in any way means to diminish the blame of the political planners who send other people’s children into war, often these days without having fought themselves. Rather, I think, her lyrical and literary rhetoric invites these soldiers, male and female, to turn inward, to reclaim a different sense of responsibility, to stir their conscience against and arouse their resistance to what President Eisenhower, on his way out of office, called the “military-industrial complex” which he saw rising up to maximize some people’s war profits. An evil that has grown exponentially since Eisenhower’s and Kennedy’s own flirtations with war in Southeast Asia.

So what about Sainte-Marie’s song? What do we make of it on this holiday designed to memorialize and honor our war dead, our veterans, and those still enrolled in our armed forces?

A utopian ideal, perhaps; given our knowledge of human psychology and of the attractions, to some men especially, of the camaraderie and adrenaline associated with a warrior culture, it seems unlikely that masses of potential soldiers all across the world will decide in unison not to fight. Our notions of patriotism, and of national exceptionalism, make it difficult to even hold a rational conversation about it. I am painfully aware, as I take up the subject, of the anger that might be provoked by simply raising the subject. As if to do so were somehow insulting and dishonoring the legacy of generations of freedom fighters.

It is not my intention to dishonor or to insult, let me just say. But given the love of freedom that we cite as the cause for all our wars, why not debate how well our military actions abroad and the actions of government and we the people at home really serve to protect those freedoms? It is worth noting, for instance, that during the Johnson and Nixon administrations in particular Buffy Sainte-Marie was considered an “artist to be suppressed” and all kinds of extravagant efforts were made, then and in subsequent years, to suppress her and other members of the antiwar movement and other civil rights causes. The situation became so bad, in fact, that between 1976 and 1992, when Sainte-Marie recorded her album Coincidence and Likely Stories (it contained incendiary songs like “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee,” which dealt explicitly with the continuing assault on Native life and culture by government, energy companies, and “the corporate bank”), she essentially stopped touring in the United States and did not record another album during more than a decade and a half.

Why all this fuss if the song – and the movement – did not carry some real weight? If its persuasive powers were not sufficient to contribute to a real disruption of the status quo? Do we really want to live in a country that, in the name of freedom, tramples on the dissenting opinions of people we may not want but possibly need to hear? Or in a country that, as is the case today in Obama’s tragically mixed legacy-in-the-making, persecutes whistle-blowers as traitors for revealing government actions that run against our most cherished ideals and illusions – of what we are taught to see as a basic American exceptionalism?

It is worth noting, too, that many of our soldiers have in the past (and continue today) to come home with awakened conscience and an antiwar passion quite their own. Among them have been the likes of Howard Zinn, controversial author of the provocative and profoundly readable A People’s History of the United States, which my former governor of Indiana Mitch Daniels was recently found to have tried, while he was still governor, to have removed from educational curricula at Indiana’s public universities. I noticed, the next time I walked into a Barnes and Noble, a table veritably stacked with copies of the latest edition, sales of which the attempt at censorship only fed. True, the book has its biases, but it helped to correct a serious imbalance in our official histories which previously had tended to make short shrift of the perspectives of our political and cultural losers.

It is worth noting, too, that many of our soldiers have in the past (and continue today) to come home with awakened conscience and an antiwar passion quite their own. Among them have been the likes of Howard Zinn, controversial author of the provocative and profoundly readable A People’s History of the United States, which my former governor of Indiana Mitch Daniels was recently found to have tried, while he was still governor, to have removed from educational curricula at Indiana’s public universities. I noticed, the next time I walked into a Barnes and Noble, a table veritably stacked with copies of the latest edition, sales of which the attempt at censorship only fed. True, the book has its biases, but it helped to correct a serious imbalance in our official histories which previously had tended to make short shrift of the perspectives of our political and cultural losers.

#

Howard Zinn, in my book, whatever his personal or professional flaws, was and remained until his recent death an American patriot. And not in spite of his radical (and arguably polemical) scholarship, but because of it. He was out to tell hidden truths and to improve by his labor the nation and the world he lived in. He even makes a brief appearance, in his capacity as a young professor and participant in the civil rights movement, in Taylor Branch’s scholarly trilogy on America in the Martin Luther King years, which I spent the past few months reading.

King is mostly known, to white audiences, as the almost mythic disassembler of our own apartheid system of Jim Crow segregation – and by the most cited passages of a single speech with its comforting assurances of the great changes, real and superficial, that have occurred since his death in 1968. The dream of little black children and little white children playing together; of a day when people would be judged not “by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character” – a sentiment, that last one, which has been used cynically by covert segregationists to kill Affirmative Action programs that sought to in small measure correct an educational and socioeconomic imbalance that still exists in our country as an inheritance from slavery. A deficit that most white Americans have had trouble understanding.

![97806848571381[1]](https://brettalansanders.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/978068485713811.jpg?w=500) But studied in its entirety, King had identified already in that speech the problems of economic and educational opportunity that keep the imbalance in place. And he was always uneasy about the escalating action in Vietnam. That’s why I was especially anxious to get to volume three of Branch’s trilogy: At Canaan’s Edge, with its increased emphasis on that conflict and on the impossibility of fully addressing President Johnson’s ambitious domestic agenda while our economic and moral energies were diverted toward determining the destiny – by force of arms, bombs, and chemical weaponry – of a dark-skinned people on the other side of the globe.

But studied in its entirety, King had identified already in that speech the problems of economic and educational opportunity that keep the imbalance in place. And he was always uneasy about the escalating action in Vietnam. That’s why I was especially anxious to get to volume three of Branch’s trilogy: At Canaan’s Edge, with its increased emphasis on that conflict and on the impossibility of fully addressing President Johnson’s ambitious domestic agenda while our economic and moral energies were diverted toward determining the destiny – by force of arms, bombs, and chemical weaponry – of a dark-skinned people on the other side of the globe.

From the beginning Dr. King’s advisors were almost unanimous in discouraging him from making public statements about the war. I have remained deeply impressed by his moral and ethical determination to be heard on that issue, nonetheless. Even though, as an almost universal lack of support made necessary, he then turned the main thrust of his organizing toward a Poor People’s March on Washington that did not take place, since a sanitation workers’ strike intervened to bring him to Memphis where he would be assassinated. The Poor People’s March, which sought to reach across all racial and geographical boundaries and was to include a contingency from the American Indian Movement as well as white Appalachian mine workers, was to his mind the next best way to get the nation’s attention on the depths of a pervasive domestic poverty. A poverty that, like problems of race and civil rights, could not be addressed while billions of dollars were being diverted to misguided foreign entanglements such as George Washington long ago warned us against.

King’s message on the Vietnam conflict was received well, at least, by those in attendance at the Riverside Church in New York where on April 4, 1967 he made his most complete statement on the issue. Outside of those walls, however, his message was roundly condemned – even among the black community that feared a backlash against the movement – and his patriotism put seriously in question.

“I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight,” King said, “because my conscience leaves me no other choice.” Citing Robert McAfee Brown’s statement that “A time comes when silence is betrayal,” King said that his ministry had become “a vocation of agony … as I have moved to break the betrayal of my own silences and to speak from the burnings of my heart.”

He said that Vietnam had “broken and eviscerated” the civil rights movement’s earlier momentum and pointed out the hypocrisy of sending black soldiers to fight, supposedly, for freedoms in Southeast Asia that their own government could not guarantee them at home. Likewise, he said he could not answer young rioters who questioned his calls for nonviolence “without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today – my own government.”

Also, on a more explicitly patriotic note, he worried that his and the President’s common efforts toward a more perfect union could not survive the contradictory hardening of a national posture for war abroad: “If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read ‘Vietnam.’” As for religious leaders’ excusing of the war’s violence: “Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them? … We are called upon to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation, for those it calls enemies. No document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.”

King’s own analysis of the historical and cultural roots of the conflict, explained in greater detail elsewhere in this book, impress me as quite astute. Certainly they have held up well to the judgment of history; or to history, at least, as related by Howard Zinn and others of a less polemical bent who have faced up to the self-delusions and official apologetics for a severely mistaken war policy and rationale. But most potent here are his words, to the congregants at Riverside, describing what it all must look like from the ground level of the South Vietnamese themselves:

“They must see Americans as strange liberators,” he said. “Now they languish under our bombs … and consider us, not their fellow Vietnamese, their real enemies. … They move sadly and apathetically as we herd them off the land of their fathers into concentration camps. … They wander into town and see thousands of children homeless, without clothes, running in packs on the streets like animals.”

“Somehow,” he then adds, “this madness must cease” (pp. 591-93).

#

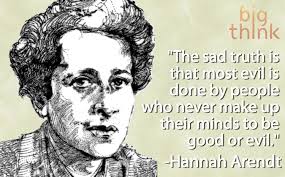

In Corey Robin’s rather lengthy and convoluted article in the June 1, 2015 issue of The Nation – “The Trials of Hannah Arendt” – he discusses, in respect to arguments pro and con in a selection of other books and commentary, her famous (and to many Jews, infamous) book Eichmann in Jerusalem. Arendt was a nonobservant Jewish political philosopher who, after witnessing the 1961 trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, declined to see him as a monstrously outsized anti-Semitic monster, instead coining the phrase “banality of evil” to characterize the unquestioning acquiescence of him and others to the machinery of genocide. To dismiss Eichmann’s crimes as banality rather than evil, or as many readers misinterpreted, to allege that he was not anti-Semitic at all, offended sensibilities more complex than I have time to go into here.

In Corey Robin’s rather lengthy and convoluted article in the June 1, 2015 issue of The Nation – “The Trials of Hannah Arendt” – he discusses, in respect to arguments pro and con in a selection of other books and commentary, her famous (and to many Jews, infamous) book Eichmann in Jerusalem. Arendt was a nonobservant Jewish political philosopher who, after witnessing the 1961 trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, declined to see him as a monstrously outsized anti-Semitic monster, instead coining the phrase “banality of evil” to characterize the unquestioning acquiescence of him and others to the machinery of genocide. To dismiss Eichmann’s crimes as banality rather than evil, or as many readers misinterpreted, to allege that he was not anti-Semitic at all, offended sensibilities more complex than I have time to go into here.

Be all that as it may, Robin argues, whatever Arendt’s errors, she was essentially correct in her overall argument and her moral or ethical sensibilities were greater than her detractors acknowledge. In fact, according to Robin, part of the intention in using the word “banality” lies in 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment, in which he argues for the need to “think from the standpoint of everyone else.”

Arendt cites several instances of the “thoughtlessness” evident in Eichmann’s complaints at his trial – in the context of millions of Jews sent to ignominious deaths by his and others’ order – about the unfairness of his own situation. “Arendt focuses on Eichmann’s cluelessness not to dramatize his inner life,” Robin writes, “but to externalize it, to give it objective form in the world.” In other words: “This inability, as Kant says … ‘to think in the place of the other person’ … ‘This kind of stupidity, it’s like talking to a brick wall. You never get any reaction, because these people never pay any attention to you.’ Such a person, she went on, is ‘infinitely worse’ and ‘incomparably more fearsome’ than a murderer who kills for passion or self-interest, ‘because he no longer has any relationship with his victim at all. He really does kill people as if they were flies.’”

Arendt elaborates further on this point in a letter to the journalist Samuel Grafton: “We resist evil by not being swept away by the surface of things, by stopping ourselves and beginning to think – that is, by reaching another dimension than the horizon of everyday life.”

I would like to suggest that in our own time, in our own place, we could use a bit less of the flag-waving patriotism that hears or sees no evil, where our great nation is concerned, and a great deal more thoughtful or mindful discussion that might bring us toward a more complete understanding of both our virtues and our vices as people and nation.

Don’t get me wrong; I don’t mean to disparage or to minimize the sacrifice of those we memorialize on this day. But I think we better serve them by looking harsh realities in the face rather than shying away from them. We give their sacrifice greater meaning – we prevent those who have died in our name from having done so in vain – by accepting the fact of our people’s and our nation’s grave errors and by taking action to see that we don’t keep making those same mistakes.

Maybe by that process we will discover that Buffy Sainte-Marie’s utopian aspirations for a universal laying down of arms, unachievable as it might be, still makes infinitely more sense as an ideal to reach for than the previous century’s wars to end all wars.

Or in our case, as seems increasingly evident, unending and borderless wars that practically dispense – entirely – with any real hope for peace in our or anyone’s time.